Resolution, Authority, and an Owl That Calls Himself King

Is that an ARPIA Game of the Year 2023 Award sitting on the table? Yes, eagle-eyed reader, it is.

PAX Australia has passed us by, and I had the opportunity to playtest a new game called The Tapestry, the intro (refined over 5-or-so playthroughs) goes something like this:

In a woodland far from here, there is a giant oak tree. Underneath that oak tree lives a community of mixed woodland critters: Mice and otters and squirrels and the like. They call the nearby river Mill Brook, the tree The Millbrook Oak, and the community underneath Millbrook Hollow. They live surrounded by a family of hawks, an narcissistic owl, a haughty viper, a devious weasel, and a wholesome raccoon. With so many predators around, for generations their survival has been dependent on their capacity to work together as a community.

In the foot of the Hollow, in the first well-dug great hall, there runs a tapestry; all the way around the inside of tree’s base. The tapestry is a living document: One end shows history, and one end is woken regularly and added to. There are patches where facts have been amended, and where things that were true have been removed. When deals are made between the community and those that live nearby, they are added to the tapestry so that all know what their role is in delivering that deal. When the community establishes new rules, they sew them into the fabric for permanence.

When you leave the Hollow’s grounds, you take a piece of the tapestry with you. When you return, it is added back to the network of threads. What changes you make to the world will be defined by the changes you make to the fabric.

And in the end, I came away with a beautiful sheet of paper, marked by a whole lot of play.

Taken at the end of game 4. This one is missing my favourite change from game 5: “We can pass through Echo’s territory” (bottom left) becomes “We can’t pass through[…]”.

Echo…was not pleased.

Accepting Resolution

The core resolution system of The Tapestry is that square of stakes in the middle. As a playtest, the details were a bit nebulous, but the general vibe was as follows:

When you need to put dice to something, decide what is at stake. Roll that many dice, divide them up into “gains and losses” (above a threshold result or below), and then assign them as you desire.

This has a lot of heritage in PSI*RUN specifically (various editions cite various authors. For simplicity we can say Meguey Baker, et al. 2011), and there’s a longer lineage from that of Otherkind Dice (which I know exists, but I haven’t read or interacted with in any meaningful way outside of PSI*RUN). When I say “decide what is at stake”, that is wholly player-decided (sometimes with gentle nudges from me as a GM). Players never have to roll a die that they don’t want to (eg players never have to roll Dying as a stake, never have to put their life on the line) but for every stake they put on the line, they get to roll another die, which increases their chance to Gain the things they really want (and also get XP and stuff like that).

The design intent here is to get players to buy-in to the consequences they face. Firstly, they buy-in because they ask to “roll it in”, and secondly they accept that stake because they are the one that assigns the die against it and decides to “eat it” (the terminology that came up on the day). And, for those who are interested, it was a complete success. Especially once each group recognised that the people who were going to have to deal with the consequences were for the most part, the group that would follow them. A real success, with more information from me to follow.

But, When Do We Resolve?

This is a question that came up during design, and comes up almost every time I design something new: When do we turn to the dice, and when don’t we? Or, as I like to think of it: When does the game interject into the conversation?

The instinctual answer here tends to be “when we disagree” or “when the outcome is unclear”. The game mechanics are a dealbreaker between “I hit you with my sword” and “I block your sword with my shield”, or any such two mutually exclusive expected outcomes. Which makes a lot of assumptions. Firstly, it makes the assumption that we have equal authority, and secondly it makes the assumption that the only reason we are using a game rule system is because we can’t agree. Neither of those need to be true.

When We Have Unequal Authority

If we assume a “traditional” RPG authority structure (that is, an authority structure present in a game of the Traditional Genre) the Player has authority over their character, and the GM over everything that is not a player character. Where those spheres of authority interact is two point source interference: They tend to be of equal power-of-assertion such that neither overpowers the other, but they both disrupt each other. The traditional conflict of “I hit you, you block” is an Equal Authority moment because your character and mine are probably of equal “power” within the game, and thus we each have an equal “right” to say what the outcome is. The Tapestry…doesn’t do that.

Conflicts requiring resolution within The Tapestry often take place where a prey animal is negotiating, pleading, misleading, or understanding a predator. The monopoly on violence, escalation, and refusal tends to be one-sided. Yes, the predators have limitations or needs, that’s why the negotiation can occur in the first place, but when our red squirrel called Harley is negotiating with King Avalon the Owl, there is no capacity for the player to “assert” an outcome. The player is not empowered to make demands of the GM through the fiction, because Avalon has the monopoly on simply flying away or tearing Harley to shreds. The communication between them is unequal, and thus so is our diegetic power-of-assertion. As the GM playing a stubborn owl, I never have to give the players the right to assert anything upon me, and nor do I ever have to ask them to roll before injuring them. As the owl, I am unburdened by their desires.

(Now, for those who are saying “but as players we get equal say”, or those saying in a trad space that the GM has more authority by virtue of being a GM, this is definitely an axis, but is much much deeper than I have space for here)

When We Cannot Agree

As a GM I am a "fan of the player's characters", often to a fault. I want players to succeed, especially when playing as little woodland critters. I want Harley to stand up to King Avalon and strike a deal (as an aside, a deal that impoverishes Millbrook Hollow, and disrupts the flow of clean water for months to come). I, as a GM, am a fan of the player’s intent and also want the same outcome. Does that mean that I shouldn’t bring dice into the conversation? If I, as a GM, want my plucky 5e adventurers to stop the evil wizard, should I not roll his dexterity saves and just say “ah, fuck it, you get him!”?

So when my desires align with yours, as players, what gives me the authority to be an advocate of “trouble”, or what I’ve taken to calling a “supportive antagonist”? From where am I allowed to say “I agree with you entirely, but Avalon doesn’t”?

Contemporary Approaches

Note that I’m far from the only person to have come up against this method of calling the game function (to paraphrase a dear old friend about object oriented game design). In Apocalypse World (Baker and Baker, 2010), the moves are specific fictional triggers and we are forced to engage with the move structure whenever we conduct those fictional triggers. We cannot deliver a threat without also rolling the dice against the “Go Aggro” move. More pointedly, in Monsterhearts 2 (Alder, 2017), our teenage characters MUST roll to Shut Someone Down when their words do that, regardless of if it was their intent or not. That game is almost defined by a set of moves that players trip over, rather than engaging with intent. We can call this method “demanding resolution”.

Powered By The Apocalypse (PbtA) games often have the most claim to Demanding Resolution, because they are the clearest in their demands. Defining narrow fictional circumstances allows the game to draw areas where it absolutely MUST be consulted without interfering too much (or, can, depending on how well those moves are written, and I’m certainly not naming those that do it poorly here). However, the Trad, Old School Renaissance (OSR), New School (NSR), and Forged in the Dark (FitD) have tended toward a softer lexical approach mostly defined by the word “dangerous” or “uncertain”. While the language is softer, this is still Demanding Resolution based off one question: Can the player refuse to roll the dice (/interact with the resolution system)?

If you want to talk about where systems make assumptions, D&D 5e (Wizards of the Coast. 2014) is always a good starting point, because it is built on 30 years of play assumptions.

The problem with the “uncertain” approach is that assumption of equal assertion: It assumes that the player swinging their sword at the dragon’s scales gets to assert that their attack hits, and that is in conflict with the GM’s assertion, and that the GM needs the added authority of dice to respond with a no. This is a notable habit of players that is hard to shake, but leads to better play experiences when you do. In the OSR, NSR, and FKR (Free Kriegsspeil Revolution - a modernisation of old wargaming practices) it creates a not-insignificant conflict where the GM’s decisions become that of a Referee (a term used often in these games) rather than a Player in themselves. That is, the Referee must have no goal greater than “truth” or “consistency”, and that their “rulings, not rules” are intended to generate a better play experience for all. The Referee model holds up well with unequal authority, as the referee is really the only authority that matters in decision-making, but creates a variable experience in how much the game gets involved, which is a Your Mileage May Vary situation. In my own experience, the OSR tends not to engage enough with the mechanics of a system, which leads to play feeling less anchored or meaningful. It leads to many situations when we all agree, and those in which we don’t agree feel the least enjoyable to involve dice (notably, combat).

The Tapestry’s Approach

I present this not because it is perfect, but for the ethnography of it all. This is how The Tapestry ended up invoking its rules during PAX Aus.

Rolling dice was an offer, never an obligation.

This is what I’m calling “Proposed Resolution”, though I’ve previous spoken about it in conversations as “oops, all saving throws”. Where Demanded Resolution says “as you have met these conditions, you must do the following”, Proposed Resolution says “if you want, we can roll some dice. Your call.” Proposed Resolution doesn’t ever demand that players roll dice, nor does it ever set a threshold that players must meet in order to roll dice. It simply puts the resolution system in the centre of the play space, places a stack of tangible objects like dice nearby, and says “Gee, rolling looks like fun, doesn’t it?”.

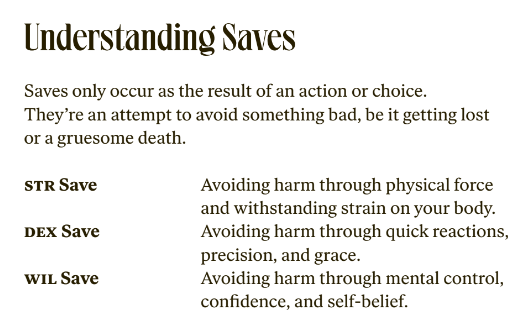

Before we go any further, I must make a reflexive statement to mention Chris McDowall’s Into the Odd Remastered (2022), which similarly uses only (or primarily) saves. This mention is perhaps the most I can offer it, as I have not played ITO itself (though I have played two games from its lineage, and was….unimpressed with them as design texts or play experiences), and Into The Odd’s text is not robust enough to really outline whether McDowall and I are talking about the same thing here (Chris, if you read this, reach out, mate. I’d love to see if we’re on similar tracks).

An interesting and effective system, but not a robust addition to the design-theory landscape, unfortunately. Just…not enough word count for it. I’d love to see this difference between a “save” and an “action roll” fleshed out more.

If Proposed Resolution is presented only as “would you like to avoid the Owl’s claws as he rends your flesh from your mousey bones” the decision is meaningless, except in the most left-field scenarios. This is why D&D is not any worse for it’s assertion of saves (“takes 3d6 damage on a failed dexterity save, or half as much on a successful one”), because there’s no cause for a player to refuse the opportunity to conduct a save.

In Tapestry, however, we wanted a reason for players to want or reject more dice, so it often ended up with pitching a middle-of-the-road scenario, and offering players to “push their luck” with a save. “Oh yeah, Hades the Firehawk will want you to feed him for two days and tend to his wounds. You could roll Resources in to talk him down, but if you put a Loss die in Resources, it’ll be a lot more than two days. How much fish can you spare?” These offers were a real joy to present and watch players accept or reject:

”You’re going to walk through Echo’s grassland even after she told you not to? Do you want to roll in Attention, here?”

”Not yet, maybe later.”

”Okay, so she won’t, like, rock up and interrupt you, but she’ll know that you’ve been there”

”Yeah, no stress. We’ll deal with Echo once we’ve sorted out Avalon. I’m more worried about the Owl anyway.”

One group dubbed these “summer problems” (as they were playing a springtime scenario). Echo is a summer problem, we don’t need to roll her in just yet.

In old 2000s game design parlance, we might call this “Yes, and” vs “no, but” vs “No, and”. The players live in No, But (“you’re spotted, but she stays in the grass just observing. It’s not disruptive to your current plan”), but can roll to reach Yes And (“you get by without being spotted and can fulfil your plan”), at the cost of No And (“you’ve been spotted and she’s going to make it a Big Deal right now”). In post-PbtA, we could call this “living in success with cost” or “Assuming 7-9”. With players rolling to steal 10+ at the risk of 6-. If I were trying to be cute, I might reference the Taking Ten rule from 3.5 D&D, I might call this “Taking 7-9”. But I won’t use a term that demands knowledge of both “historical” RPGs and also modern ones and give the idea so much baggage. But I could, just so that you understand my position here.

The beauty as a GM (who wants a world that increases in complication as players act) is that I can propose a handful of issues and check the player’s reactions for whether I’m on track that this is a threat worthy of their heroics (cf my ongoing obsession with Swords Without Master). Their capacity to reject my offers to “roll to make it easier on you” was as much a buy-in to the complications of the setting as it was a negotiation of what troubles they wanted to face in our short session.

The benefit of Proposed Resolution, in whole or part, is that players only ever lose what they’ve told you they’re willing to lose, and they can never gain without putting something on the line.

Future Design Space

The Tapestry is a great project, and one that will be released in some form in Q1 2024. Most importantly though, this has given me some design space that I’ve wanted for a future Sci-Fi Project.

For a while I’ve been fiddling with EXiST, a portal-fiction sci-fi game. There’s about 4-ish starkly different versions of it, and my issue always came down to the act of resolution. I didn’t want the game to be “roll a d20” or “build a dice pool based on skills”, with some yes/no resolution. Instead, I want to ask players what they’re willing to spend:

Player - I shoot that post-nuclear mutated alligator!

GM - With your standard sidearm? No, you won’t kill it, but you do slow it down, or it does keep its distance.

Player - Mmm. What if I [spend my spare mag item to dump round after round in its mouth]/[use my armour piercing specialist ammo instead]/[toss a grenade]/[throw a ration to distract it]/[eat the ration to get the burst of speed i need to escape from this alligator].

I want to test out what it means to have players tactically consume their military gear as they explore incredibly dangerous scenarios.

Expected Questions

Isn’t this position and effect from FiTD? Maybe? I don’t think so. It feels different to me. The key difference would be that FitD is still a demanded resolution. You can’t “buy success” at any level. Even Controlled Great you still have to toss the bones. The difference with Proposed Resolution is that the player can choose not to push their luck and take a known outcome that is tolerable. FitD is usually more dynamic and pushes toward really dangerous situations that can’t sell a middle-ground.

Isn’t this just FKR with extra steps? Isn’t everything just FKR with extra steps? Like, I don’t think this is wrong, but those extra steps mean a LOT to the play experience here.

What if players just refuse to engage with the resolution system? Then something is wrong between the player and the system. It wasn’t what I saw in Tapestry, and I don’t think it’s what I’ll see in the next projects either. Players want to roll dice, and for the most part are willing to give up stuff to get the chance at victory. In fact, a conversation with an established designer once had them warning me that it may actually go the other way: That players would be so willing to buy into a lot of danger, and will then feel bad about it when its delivered. We’ll keep an eye on all parts.

What happens when I run out of resources to burn? Well, theoretically, that shouldn’t happen. That’s the great thing about Community in Tapestry, you can always make it a Summer Problem. You can always push the deal with King Avalon the Owl to be bigger and more costly if delivered later. One of my mouse players commented that a deal with Avalon that required delivery the next year and year after was “a problem for our children and grandchildren”.

Doesn’t it feel bad to always be told no? Absolutely. This is definitely a framing risk. It worked in Tapestry because the setting sold the players as being weak woodland prey in a world of predators. Their assumed state was abject failure, flesh torn from bones, or being swallowed whole. Mice are not expected to overcome a Viper. That’s something worth watching in the next project: How do we pitch the “difficulty” of the world (cf: the equal authority problem in D&D 5e).

Why this and not FitD/FKR/OSR/ITO/Other Games? Because I want a different emotional play experience. Primarily, I want players to feel like they drove the situation into being responsible for their own successes and failures, and actively deciding what they’re willing to put on the line. I want players to feel “tactical” in their success, and participatory in their failure.

What do you do about a player that is intellectually dishonest about what is at stake, or what is being offered? Mate, you do the same thing you always do. You consult the flowchart.