37. Fortune Rolls - You Think You’re Better Than God?

At the resolution of our previous Episode, I promised that we would discuss why the change in GM Authority between Apocalypse World 2nd Edition (Baker & Baker, 2011) and Blades in the Dark presupposes the introduction of the Fortune Roll. Why God does not play dice with the universe, but you might have to.

We’ve already established that the two systems view the process of creating a narrative story world through different lenses, even when they both refer to Fiction-First approaches. One of the fundamentals differences is the approach to delegation of authority. Blades is specific that “No one is in charge of the story”

The GM presents the fictional situation in which the player characters find themselves. The players determine the actions of their characters in response to the situation. The GM and the players together judge how the game systems are engaged. The outcomes of the mechanics then change the situation, leading into a new phase of the conversation—new situations, new actions, new judgments, new rolls—creating an ongoing fiction and building “the story” of the game, organically, from a series of discrete moments. No one is in charge of the story. The story is what happens as a result of the situation presented by the GM, the actions the characters take, the outcomes of the mechanics, and the consequences that result. The story emerges from the unpredictable collision of all of these elements. You play to find out what the story will be

The Conversation - Blades in the Dark p6

I want to contrast this with the assertions made by AW2e:

You probably know this already: roleplaying is a conversation. You and the other players go back and forth, talking about these fictional characters in their fictional circumstances doing whatever it is that they do. Like any conversation, you take turns, but it’s not like taking turns, right? Sometimes you talk over each other, interrupt, build on each others’ ideas, monopolize and hold forth. All fine. these rules mediate the conversation. They kick in when someone says some particular things, and they impose constraints on what everyone should say after. Makes sense, right?

The Conversation - AW2e p9 (Baker & Baker, 2011)

Generally, the Bakers are more welcoming the messy nature of socially-facilitated human interaction, with interruption and monopolization as offered actions. Blades is less concerned with socially-facilitated interaction, and instead uses the structures of delegated authority to turn what AW2e calls “[taking] turns, but it’s not like taking turns, right?” into “judgement calls” (more on Judgement Calls here). Blades does what a lot of modern participatory co-design approaches do these days: Participatory Co-Design.

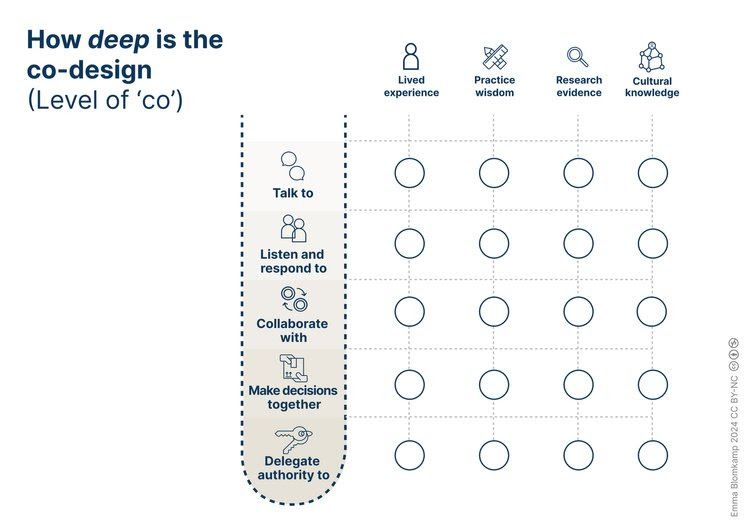

“Level of ‘Co’” by Dr Emma Blomkamp (2024), one of the most fascinating co-design researchers on the planet

Co-Design seeks to connect experts, users, stakeholders, and decision-makers together into a shared and collaborative process. The intent is that by involving everyone in the design process (collaboratively designing), we generate more real-world useable designs, and therefore systems. There are different degrees to which we can co-design (what Blomkamp, 2024 calls “depth”), and it is often expressed that deeper is better (I’m not sold on that personally, and Singh et al. 2023 over up a number of good reasons as to why maximum depth co-design isn’t always an easy state to achieve, and arguably not desirable). The key, for this discussion, is that deep Co-Design also requires Co-Creation: The assignment of decision-making authority away from normal hierarchies and into the hands of these other groups — Giving players a feeling of ownership by actually delegating them authority to decide what is true in your system or setting.

The reality is that in games, sometimes we want to deeply co-design at the level of absolute delegated authority, and sometimes we just want to self-express and be heard without having to perform the systemic heavy lifting of deep co-creation.[1] I don’t have to create a ton of narrative to play 5e. I just get to rock up and the game makes me feel cool and strong. I am not a co-creator as a player of (most) 5e games, I’m a consumer. Our relationship, then, is one with a service-delivery and expertise-gap. You are the brilliant dungeon master who has crafted me a world, I just rock up, choose which skill to use, and throw some dice at the table. The difference between these approaches (as with co-design) is not explicitly better or worse.[2]

[1] - I considered linking out to a few games here, but in each case it felt like either an initiation to argument (“well, our One Ring game gave players HEAPS of delegated authority”), or a criticism. It is neither, and so the direct examples beyond 5e are left to the reader’s own analysis.

[2] — Often, though not always, traditional heirachical designs will be worse experiences than co-design (in games and healthcare and other fields). This isn’t because the process itself produces worse games, but because games that are produced by “industry standard” approaches without intentional validation are often missing the level of care that will come from a professional and responsible co-design approach. That is to say: Good trad games with good groups make good games, and just because it’s on itch.io with a Belonging Outside Belonging tag (or, god forbit, a game Descended from the Queen), doesn’t mean it’ll be a rewarding play experience.

Okay, so, Fortune Rolls.

Blades in the Dark does not allow space for creation without interfacing with the co-design process. There are steps that must be approached before decisions can be made, a process that undoubtedly empowers players both as narrative co-creators, and also as advocates for Player Characters. Blades, unlike AW2e, does not allow a GM to simple say that things “are”.

Potential fiction is everything in your head that you haven’t put into play yet. It’s a “cloud” of possible things, organized according to the current situation. […] As the players take action and face obstacles, you grab elements from the potential fiction cloud and establish them in the ongoing scene. Once established, they can be leveraged by the players. They’re a part of the game. Before that, they’re just notional—they don’t have a concrete “place” in the game yet. They can be freely incorporated as needed to address the results of rolls and to paint the picture of the ongoing operation as it hurtles toward its resolution

GM Best Practices - Blades in the Dark p195

Always Say

• What the principles demand (as follow).

• What the rules demand.

• What your prep demands.

• What honesty demands.

[…]

Always be scrupulous, even generous, with the truth. The players depend on you to give them real information they can really use, about their characters’ surroundings, about what’s happening when and where. Same with the game’s rules: play with integrity and an open hand.Always Say - Apocalypse World 2nd Edition p81

Apocalypse World 2nd Edition identifies a notion of “truth” that Blades rejects. If, in AW2e, you have Prepped that Keeler is out of water, it doesn’t matter how well the player rolls to manipulate or threaten some water out of Keeler, it just ain’t happening. In Blades, that’s just potential fiction until it’s leveraged.

This is why the Fortune Roll is important — it isn’t really about disclaiming, as I said last ep, and as John leads off the chapter, not in the way AW2e means it, at least.

“The fortune roll is a tool the GM can use to disclaim decision making.”

[3] Obviously I love, adore, and admire John, and my interpretation and reframing of disclaiming here doesn’t make John a liar. They’re wonderful, and if they ever read this, I’m sure they would understand the position from which a lil jokey joke comes. This is very much jovially punching up at one of my design heroes.

In AW2e, the Bakers refer to “disclaiming decision-making” as the handing off a piece of fiction that “you’d prefer not to decide by personal whim”. For some more amazing writing on this, check out D’Angelo’s 2017 work on the subject. The disclaiming from AW2e, importantly, is not to dice, but rather to other realities of the story world.

“The game gives you four key tools you can use to disclaim responsibility: you can put it in your NPCs’ hands, you can put it in the players’ hands, you can create a countdown, or you can make it a stakes question”

MC Principles, AW2e p87

This gives MCs four frames to make a decision “with integrity”:

An NPC’s motivations and actions (“ask yourself, in this circumstance, is Birdie really going to kill her? If the answer’s yes, she dies. If it’s no, she lives.”)

The player’s response to the position (“Dou’s been shot. […] What do you do? If the character helps her, she lives; if the character doesn’t or cant, she dies.”)

A concrete plan (“Sketch a quick countdown clock. Mark 9:00 with “she gets hurt”, 12:00 with “she dies”. Tick it up every time she goes into danger.”)

or by placing it as a consequence of the story’s momentum (“Now you’ve promised yourself not to just answer it yourself, yes or no. Whenever it comes up, you must give the answer over to [the stake-holders of play], no cheating.”) (ibid.)

In each case the MC is still making decisions, is still authoring narrative. Arguably, with the exclusion of the “player’s hands”, they’re still doing it alone, without co-design principles. But (as I said in an earlier footnote), it brings intentionality, which removes the lazy by-whim decision-making that can fracture a story world. The reason it’s called “disclaiming decision-making” then, is that the MC is still making the decision, they’re just not taking responsibility. It’s “that’s what my character would do”, but with a bit of self-awareness and an intention to provide a better experience (and, honestly, that’s enough for me). The MC doesn’t disclaim the decision, the disclaim the responsibility for the decision. There’s a subtle different there.

Blades offers the GM no such power to make decisions, and thus no such need to disclaim the responsibility for it. Sure, sure, GMs can “judge” position and effect, they can suggest that consequences come to pass, but this is all a suggestion until the players accept it (by choosing not to push or trade or resist or any of the other myriad social and mechanical interventions Blades offers players). This is that difference between Protentional Fiction and Established Fiction: the ‘cloud’ is meaningless until the players can leverage it, and then it exists only as it needs to in order to support (or oppose) their leverage.

Einstein famously said that “God does not play dice with the universe” (or, in honour of some newlyweds I know, “Gott würfelt nicht!”). He was responding to the Copenhagen Interpretation (“a system is in all of its allowable states at once until it is measured, wherein it resolves to a single state: The one which was just measured”) and basically refused to believe that degree of uncertainty was sustainable. “God does not play dice” is an assertion that there must be some underlying reality that is influential enough upon quantum states that Copenhagen isn’t true. The universe is deterministic, not uncertain.

Now, I bring up the fuzzy headed tongue-poker because Baker & Baker’s 2011 approach aligns with him: The story world that we’ve created must have enough reality in it somewhere that we can make a decision “with integrity”. Blades does not agree. It is telling that Blades’ Fortune Roll opens with 1 die “for luck”, a premise that is not afforded to action rolls or healing or many other dice pools in the game: John believes that the universe of Blades is uncertain, and that luck is a (quantum) motivating force on how it presents to the players and characters alike. Vincent Baker has described AW2e as a system that inevitably drives to violence and ruin (while I can’t find the quote I’m chasing for that, I can offer “it’s your job to create a fractured, tilting landscape of inequalities, incompatible interests, PC-NPC-PC triangles, untenable arrangements […] an unstable mass, already charged with potential energy and ready to split and slide, not a mass at rest.” AW2e p97). This is what an Apocalypse is according to Baker & Baker (or, at least, one version of it).Worldwide flooding, catastrophic climate change, meteors, the great freeze: These aren’t things that define an apocalypse. They’re just conditions. An Apocalypse is scarcity, greed, manipulation, revenge, and positioning yourself around “violence as established”. An Apocalypse is an unstable mass, ready to split with nuclear results.

If the PCs don’t interfere with this instability (and, often, even when they do) the World of your Apocalypse will expend that potential energy with which it’s charged, and it will “split and slide” to a new state of precipitous failure. There is no luck to Apocalypse World, there is only truth (certainty), and that truth is told through the MC’s mantra: “there are no status quos in Apocalypse World” (Baker & Baker, 2011, p83, 86, 97, and 194).

In Blades, however, it may turn out okay. Things may resolve. Cooler heads may prevail. The system may settle. And that’s because, while Blades is a setting full to the brim of dynamic people and vicious motivations, those things aren’t threats until “you grab elements from the potential fiction cloud and establish them in the ongoing scene. Once established, they can be leveraged by the players. They’re a part of the game. Before that, they’re just notional—they don’t have a concrete “place” in the game yet” (BitD p195, again). Blades and Duskvol are not doomed to certain death by a resource dearth and strength-from-violence as any Apocalypse World Hardhold is. Blades (as a system) is not charged with potential energy that the players should be trying to constrain. Instead, Blades is a system and a setting of uncertainty and opportunity. Sometimes, the obvious result is the true one, and sometimes the easy answer is correct. That’s the “Hard Six” that Blades promises continually: It might all be okay. You might get away with this. You just need to dig that hole a little deeper, and then you’ll be out of it. Just one more score, and everything can be solved. Maybe.

No, if you’re wondering where Blades is getting its version of “an unstable mass, already charged with potential energy, and ready to split and slide”, it’s the Player Characters. In Blades, the Player Characters are the apocalypse.

Mark Experience,

Sidney Icarus

The header image for this post is "like the gods rolling the dice" by Musicaloris is licensed under CC BY 2.0.